Queer Reasoning

Not for failure to pay rent.

Rather, the City Council voted overwhelmingly to kick the Scouts out unless they either "[reversed] the national Boy Scouts of America's ban on gays serving in the ranks or as scoutmasters ..."

One would think that a local organization that gets 56,000 boys, many without father figures, to "spend countless hours cleaning parks, running food drives, and organizing meals for the needy" would be something to laud, not ostracize.

The alternative: start coughing up the "market" rent of $200,000 per year. Despite the fact that:

For the past 80 years, the scouts have leased their corner lot off of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway for a nominal fee. And they have made the site their own by building a three-story 8,928-square-foot Italian Renaissance-style headquarters with private funds. ... And each year they spend about $60,000 on maintenance. In 1994, they spent $2.6 million on renovations.What started this exercise in nose cutting and face spiting was the US Supreme Court decision in 2000 that the Boy Scouts, a private organization, could exclude homosexuals.

Following the ruling, local governments and organizations across the country took aim at the scouts.To some degree, the Scouts have brought this upon themselves. By characterizing homosexuality as a choice, by definition morally wrong, the Scouts have both painted themselves into a rapidly shrinking corner, as well as handing their opponents the stick with which to beat the Scouts.

The Philadelphia chapter lost annual six-figure donations from the United Way and the Pew Charitable Trusts, according to Mark Chilutti, vice chairman of the Cradle of Liberty Council.

Far better to take the gay argument as given: homosexuality is innate, no more a choice than left handedness or hair color; however, it is an unchosen characteristic with real consequences. That would allow the Boy Scouts to exclude gays for the same reason they exclude Girl Scouts: sorry, wrong gender.

Just as girls are characteristically different than boys, gays are different, also. Gender is more than just plumbing. It makes no more sense to excoriate the Boy Scouts for excluding girls, or vice versa, than it does to start grabbing torches and pitch forks for the Girl Scouts decision to also exclude gays.

Or for that matter, the Girl Scouts excluding male scoutmasters, never mind making it nearly impossible for fathers to accompany their daughters on Girl Scout camping expeditions.

The only difference among these is that only one is being pilloried at the altar of phantom equality.

The Boy Scouts could do themselves no end of good by ditching religiously derived nonsense in favor of reality, then hoisting their opponents upon their own arguments.

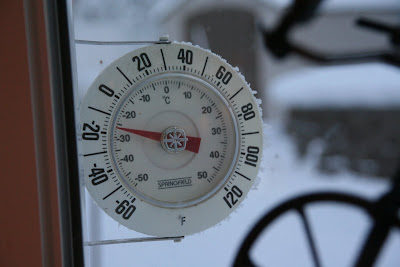

Of course, the outcome would be the same. Pity the City Council, whose collective IQs would leave a room decidedly chilly, can't figure that out.

Full disclosure: My son is a Boy Scout, and my wife is secretary for the troop.